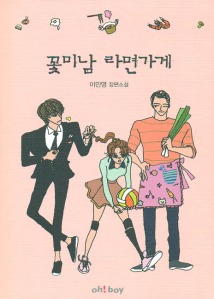

The next book we are going to discuss is Minyeong Lee’s romantic comedy Flower Boy Ramen Shop (이민영의 “꽃미남 라면가게”) from South Korea. The book is available in the original Korean here, and I am not aware of any English translation:

https://koreanbookcenter.us/product.asp?isbn=9788984315327

First, a word on the English translation of the title, which is the name of a restaurant in the novel. Typically, I think 꽃미남 (kkotminam) is translated “flower boys,” and it certainly is translated this way for the TV show related to this novel. While this isn’t a terrible translation, the word literally in Korean is 꽃 (kkot) “flower” and 미남 (minam) “good-looking man”. The use of “boy” instead of “man” is problematic in an American context where calling an adult, non-white man a “boy” has been historically considered an insult, especially during the slave era.

I can’t come up with many instances where we use “boy” for a grown man that doesn’t have at least a slightly negative connotation: “boys will be boys,” “good old boys club,” etc. “Fanboys” isn’t necessarily as negative, but it can be, and it does imply a certain amount of immaturity. Maybe there’s more neutral usage in some casual military terminology. The use of “girls” for adult women is less problematic and far more neutral, though there has been some objection to that in recent years as well.

My personal preference for this translation is the more dignified “flower men,” however in the context of this book, the majority of the male characters are late high school age, around 18 or 19, and it would be fine to call them “boys,” but one major male character is 31. I think calling adult men over college age “boys” would be much more questionable. Perhaps readers from Australia or the UK can comment on how the original English translation would sound in their countries for comparison.

Another issue raised by the “flower boys” is a clash in concepts over what defines manliness. In the modern West, there has been a lot of discussion of “metrosexual” men versus what some people consider a more traditional, narrower expression of manhood. A similar discussion is also taking place in East Asia, as this article “China, too, worries that boys are being left behind” by Lara Farrar, explains:

http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2013/09/23/202917/china-too-worries-that-boys-are.html

The main point here is that boys are trailing girls in school and have many challenges in stepping up to act manly. It raises some ironic points about “China’s exam-based education system,” which has actually been a feature for centuries, as we saw in an earlier series I did on The Scholars. Chinese attitudes toward schooling changed drastically under Mao, who was much more anti-intellectual, so there was a cultural break with the scholarly tradition men followed in the dynastic era which also could be contributing to this modern problem.

The article also references the “flower boys” of South Korea and how that relates to these concerns:

A substantial overlay of cultural conflict colors the concerns. Some people here blame the popularity of television shows and movies from South Korea that portray men as skinny with beautifully delicate features for changing notions of masculinity….

“I think Chinese women, especially young women in cities, some of them share this kind of preference,” said Song Geng, an associate professor at the University of Hong Kong who’s the author of the forthcoming book “Men and Masculinities in Contemporary China.” “This gives rise to feminized male pop stars and similar images on TV.” …

“Now on campus, the boys who look more girly are more popular,” said Wan, the student. “I think it is a trend.”

There are historical roots for this conflict. In plays from China’s dynastic period, gentle male scholars – instead of warriors – were the ones who won women’s hearts. “The sword-wielding guy never does,” said Kam Louie, the author of “Theorizing Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China.”…

Now, however, Louis said, the pendulum is swinging back toward a broader definition of what makes a man a man. “There is a traditional background in the Chinese case, which makes the revival easier,” he said. “It is not seen as being a sissy.”

But it still engenders conflict, something that some scholars say has become more controversial than it should be.

Korea also has its own historical roots for a less macho male image in the ancient Hwarang. Here is the basic background on that group of warriors from “History of the Hwarang, Korea’s Warrior Knights” by North Austin Tae Kwan Do:

http://www.natkd.com/legend_of_the_hwarung.htm

The most important points from the explanation given there are included in this quote:

Historians have been fascinated by the Hwarang in recent years. While there is significant historical material concerning the Hwarang warriors as an institution, there are still considerable mystery and speculation as to their function. We do know that generals from the Silla period – which took place from BC 57- 935 AD; Korean Silla Founder King Hyok Gosoi 1 to Korean Silla 56th King Kyongsun 9 – claimed early training with the Hwarang movement. Probably because of this, the Hwarang have become known as “Korean Silla knighthood,” with the word hwarang often being translated as “flower knights,” though it literally means “flower of manhood,” or “flowering manhood.”…

The Hwarang were a group of aristocratic young men who gathered to study, play and learn the arts of war. Though the Hwarang were not a part of the regular army, their military spirit, their sense of loyalty to king and nation, and their bravery on the battlefield contributed greatly to the power of the Silla army….They were highly literate, and they composed ritual songs and performed ritual dances whose purpose was to pray for the country’s welfare. They also involved themselves directly in intellectual and political affairs….

The Hwarang are also portrayed in K-Drama “Queen Seonduk,” where they are at one point featured putting on their ritual makeup in anticipation of dying in battle. They can also be found in historical documents such as the Samguk Sagi, which explains their origins: in the beginning, the Hwarang was a group of beautiful women led by Nammo and Chunjǒng, and the women’s rivalry led Chunjǒng to murder Nammo. Chunjǒng was put to death, the group was dispersed, and handsome young men were chosen instead to make up the new Hwarang. “Faces made up and beautifully dressed, they were respected as hwarang, and men of various sorts gathered around them like clouds.” (From Sources of Korean Tradition, Volume One: From Early Times Through the Sixteenth Century, edited by Peter H. Lee and Wm. Theodore De Bary, p.55.)

In modern Korea, the “flower boys” are known for their beauty, attention to their appearance, and other choices typically assumed to be feminine, such as wearing pink or carrying a purse. It is definitely the Eastern version of the Western metrosexual man referenced earlier, and in East Asia it carries no homosexual overtones. Like the similar struggle over the mommy wars for women, there is a great deal of controversy over definitions of masculinity in modern times, but since not all men are the same, it doesn’t seem fair to expect them to conform to a narrow definition of authentic masculinity based on appearance, talents or interests. The “flower boys” are one symbol of this conflict.

However, in the context of the novel this series will cover, I think the author isn’t particularly concerned about this controversy. The novel is a playful story about the potential romance between a woman and her two metrosexual suitors. But it’s still good to know where the term and character type comes from.

Part one of a five part series.